Learning chord theory is essential to understanding how our favourite songs work – Let’s dive in & explore!

Over 100,000 guitar-learners get our world-class guitar tips & tutorials sent straight to their inbox:

Click here to join them

Get our best guitar tips & videos

In this free lesson you will learn…

- What a chord is

- What makes chords sound similar or different

- How to map chords to the guitar

- How to build chords using their formulas

Welcome To Chord Theory!

Guitar seems so easy at first, at least in hindsight.

You get a bunch of chord diagrams, you get used to figuring out how to make those shapes, and you start putting those shapes in different sequences on the guitar.

Honestly, there’s no requirement anywhere that any guitarist ever learn anything beyond how to make chord shapes and how to use chord charts.

At some point, though, you get curious, right?

Why do these chords keep showing up? What do these shapes mean?

In this chord theory lesson, we’re going to break it down so you’ll understand how to answer the following questions:

- What exactly is a chord?

- What makes chords sound similar or different?

- Why did they give so many chords practically the same name?

- How do I map all these chords to the guitar?

Keep your guitar close so you can play these ideas as we go through them.

Chord Theory: Characteristics Of A Chord

The term chord is inherently confusing because it seems to mean a lot of things.

A string is sometimes referred to as a cord, and a chord is comprised of multiple notes.

It doesn’t help that in music, people tend to throw a lot of jargon around.

- So let’s straighten it out. A chord by definition is a specific grouping of three or more notes.

- Two notes, and you have some kind of harmony, but you don’t have sufficient context to call it a chord.

If the idea of notes or tones is already spinning your head a little bit, take a break and check out this lesson: Guitar Notes Explained: A Guide for Beginners

Three-note chords are the most basic, and they are sometimes called triads. There are five types of triads – major, minor, diminished, augmented, and suspended – but we’re going to start with the first two because they are basic structural chords, unlike the others.

Major Chord Theory

You can already tell the difference between major chords and minor chords.

Simply put, major chords sound happy and minor chords sound sad.

To get the label “major” or “minor,” chords have to be built the same way, meaning the relationships between the notes in the chords has to be the same.

The fundamental principle of chord theory is that notes in chords are named based on their relationship to each other:

- Root: the note the chord is named after, the foundation of the chord

- Third: the note that is two alphabet spaces away from the root, the note that tells your ear whether the chord is major or minor

- Fifth: the note that is four alphabet spaces away from the root, the stabilizer note that gives the necessary context to the chord

The only note that changes between a major and minor chord is the third.

It’s called a major third, and therefore a major chord, when the third is four half-steps away from the root.

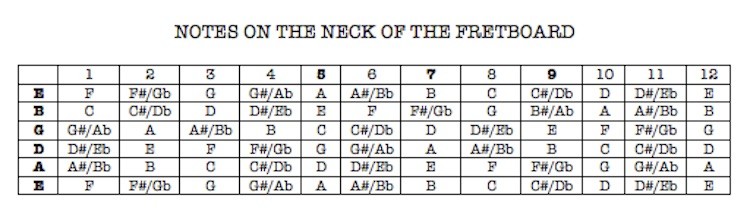

Half-steps? Alphabet? If any of that is confusing, in addition to the lesson linked above, it’s explained (slightly differently, always helpful!) in this lesson: Notes on a Guitar: Unlocking the Fretboard

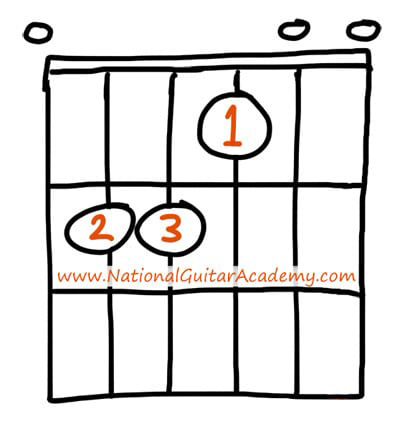

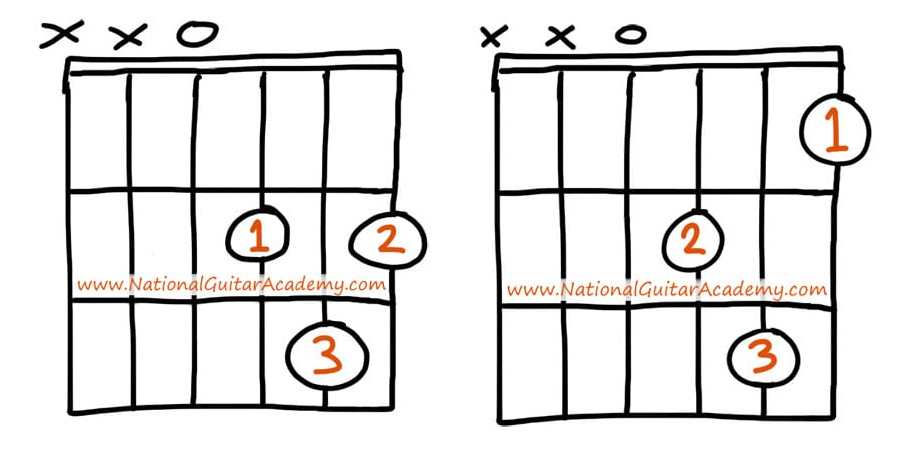

E major (022100)

E minor (022000)

Check out these two chords, clearly illustrating the difference between a major and minor chord.

The E major chord uses all six strings of the guitar, but there are only three different notes being played:

E, B, E, G#, B, E.

Put them in music-alphabetical order starting with the root, and you have E, G#, B.

Whenever you have any combination of E, G#, and B, in whatever order on the guitar, you have an E major chord!

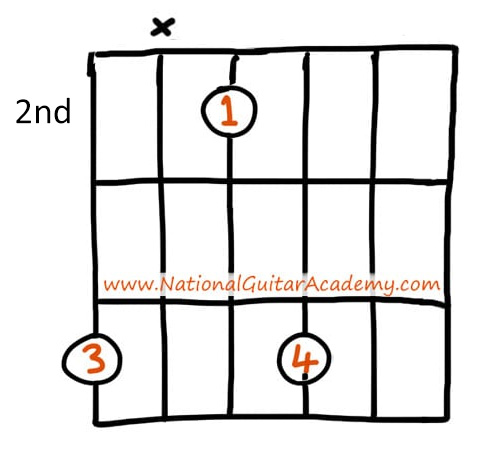

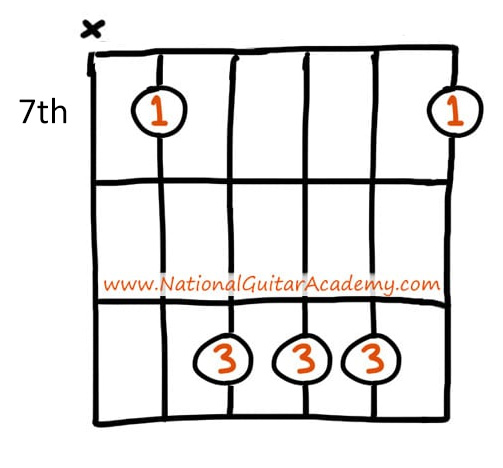

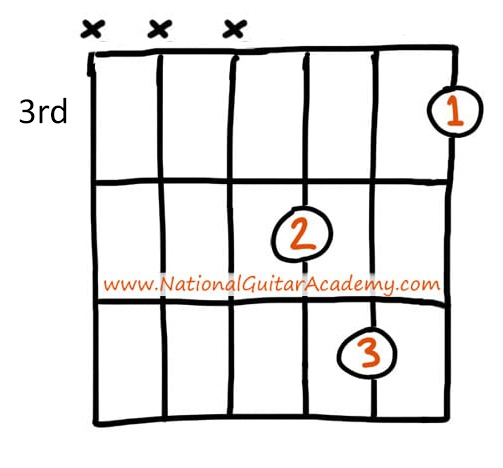

E/G# (4×2400)

E (x79997)

E (xxx454)

Play these chord shapes. Notice how they all sound the same, only with the notes in a different order? They are all the E major chord, and the difference in note order is called voicing.

For example, if you take the above D-shaped E major chord and move it up the neck three frets, you’ll have a D-shaped G major chord!

Learn 12 EASY beginner chords with our popular guide

Where should we send it?

✅ Stop struggling. Start making music.

✅ Learn beginner-friendly versions of every chord.

This is our most popular guide and it will improve your chord ability quickly! 😎

Get your own personalised guitar-learning plan 🎸

Get a custom guitar-learning plan here: Click here for GuitarMetrics™

World-Class Guitar Courses 🌎

Learn from the world's best guitar educators: Click here for our guitar courses

Minor Chord Theory

With minor chords, there is also a root, third, and fifth.

If you look at the E major and E minor chords above, you’ll see that there’s only one thing that’s different.

There are still three Es and two Bs, so the root and the fifth between a parallel (same-root) major and minor chord stay the same.

The only difference is that the third goes down a fret. All the action is on the G string. In E major, you have a finger on the first fret, so you’re playing a G#. In E minor, the G string is open.

One fret makes a huge difference! Check out these other chord comparisons:

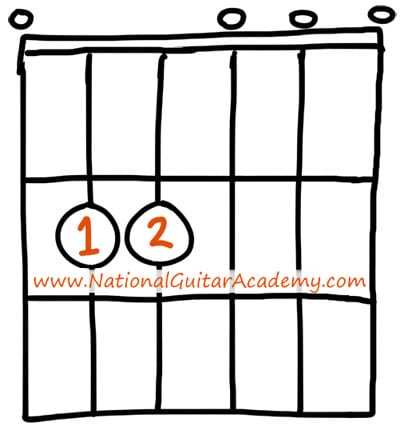

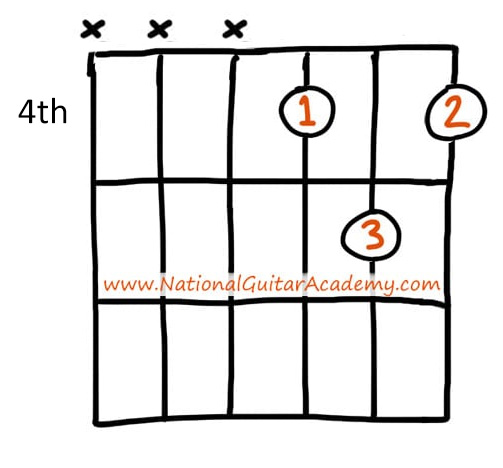

D major (xx0232) next to D minor (xx0231)

A major (x02220) next to A minor (x02210)

With minor chords, the third is three half-steps up from the root.

This makes the notes in the E minor chord E, G, B.

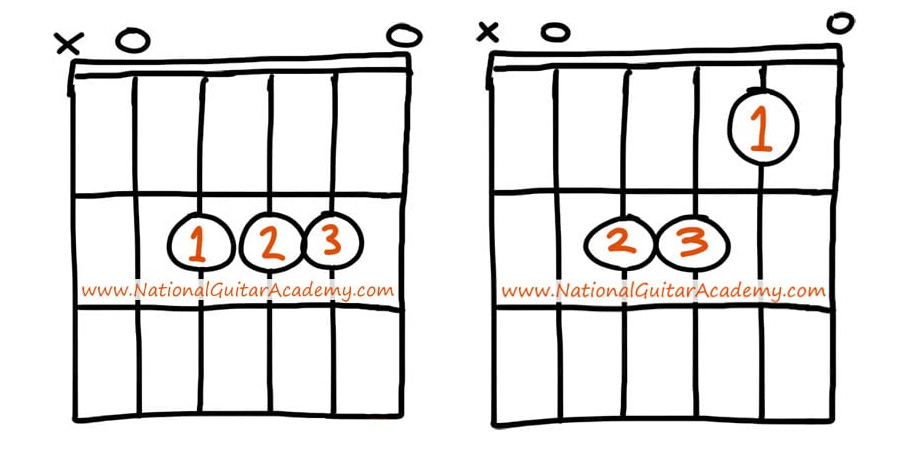

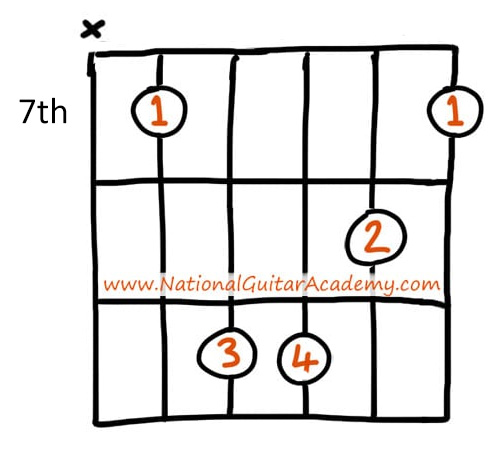

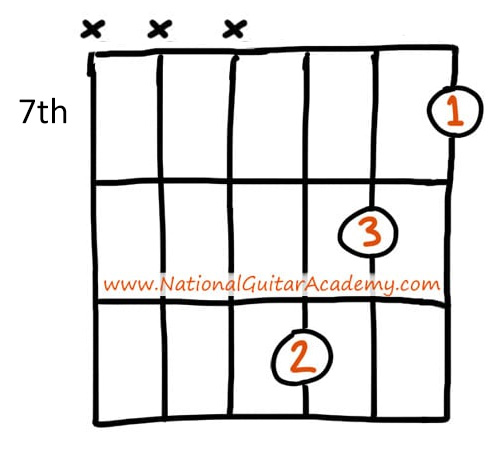

Here are some other voicings of the E minor chord.

E minor (x79987)

E minor (xxx453)

E minor (xxx987)

To figure out the names of the notes in any major or minor chord, there’s a formula you can use. From the root, count up three half-steps to find the minor third for a minor chord. Or count up four half-steps to find the major third for a major chord.

To find the fifth, count up seven half-steps from the root.

The fifth is the same whether you are playing a major or minor chord.

Pro-Tip: Stuck choosing between a sharp or flat name for a note?

Two things will straighten that out.

- First, you’re always skipping over one letter in the musical alphabet. In a D major chord, for example, the third is named F# (D-E-F), not Gb.

- Second, guitars are mostly designed to be played in “sharp” keys, so the odds are that it’s a sharp name.

Okay, But What Are All Those Numbers?

We’re not playing guitar very long before we’re called upon to play some chords with some indecipherable names involving numbers and strange symbols..

The same numbering system that gives you chord-tone names like “third” and “fifth” is the source of numbers you might see like 7, b9, 6/9, and 13.

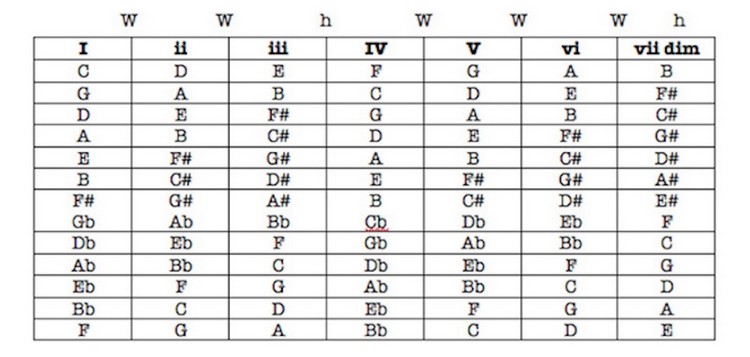

- It’s all based on the major scale – the Do-Re-Mi sequence of notes that forms the entire structure of music theory, including chord theory in Western tonal music from Bach to Beyonce.

- As a matter of fact, major chords are made up of the first, third, and fifth notes of the major scale, or 1, 3, 5 (I, III, V)

- Just as though notes were letters and chords were words, this system of numbering is called spelling.

Here’s a major scale diagram to show you how spelling works.

If you look across the row, you’ll see all the notes in the major scale, numbered with Roman numerals. Even though they are scales, they are essential to chord theory.

The Roman numerals have to do with families of chords. We’ll get to those in a different lesson, but for right now, we’re going to use the numbers to spell different chords.

In this spelling system, major chords are spelled 1, 3, 5.

- Minor chords are spelled 1, b3, 5. That means you’ll find the 3 and take it down a half-step.

- For example: In the G chord, the 3 is B, and in the G minor chord, the 3 is Bb.

- In the D chord, the 3 is F#, and in the D minor chord, the 3 is F.

Sixth Chord Theory

Perhaps you’ve seen a D6, a G6, or a Bm6. Wondered what the 6 means in chord theory?

It’s as simple as using the major scale chart above.

- A sixth chord – G6, for example – is a major chord with one note added. That note is the 6 of G, so if G is 1, or the root, then E is 6.

- Looking at the G major scale, the G6 chord is spelled 1, 3, 5, 6. The notes are G, B, D, and E.

- Listen all the way to the end of “Help” by The Beatles to hear a sixth chord in the vocals – that last little shift when they sing “oo” is a sixth chord. It’s a very Beatlesy sound!